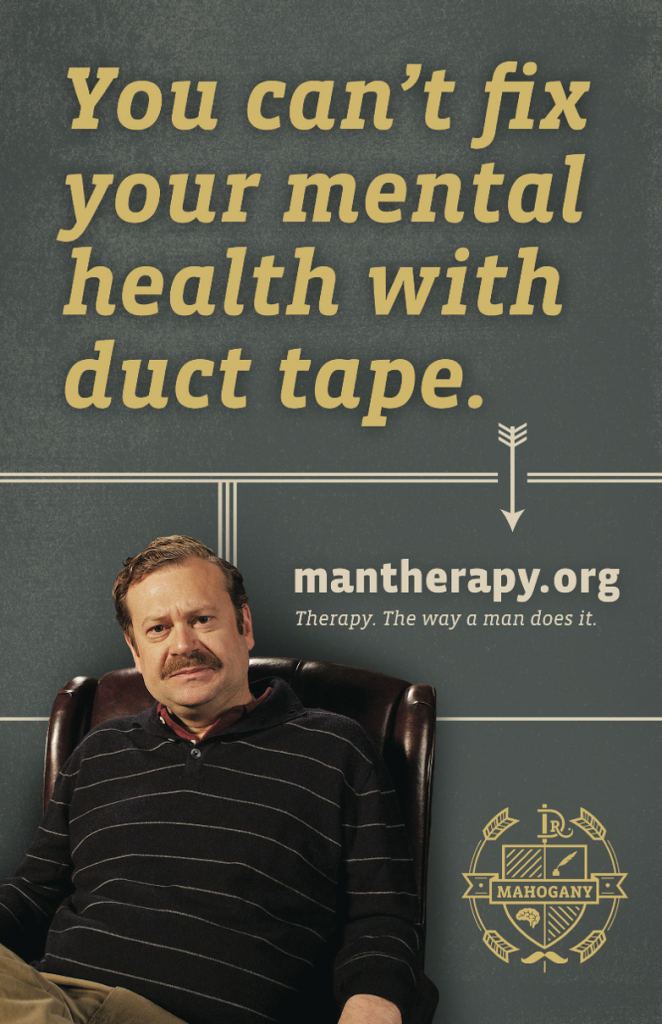

“You can’t fix your mental health with duct tape,” advises Dr. Richard Mahogany, a fictional therapist who is “manning up” mental health at www.ManTherapy.org.

The following is according to Mental Health America.

- 1-in-5 men develop alcohol dependence in their lifetime.

- Men are four times more likely to die of suicide than women are.

- Over 6 million men live with depression each year. Male depression often goes undetected because men are less likely to report symptoms of sadness and more likely to experience irritability and agitation when they are mentally unwell. This difference usually means women are more likely to get offered support, and men are more likely to get in trouble.

Men, Depression, and Help-Seeking

After losing my brother to suicide, I was on a mission. No one ever told me that the prototypical person to die of suicide was someone like Carson—a white, working-aged man. I wanted to understand why all these men were falling through the cracks and what could be done to stop this preventable form of death.

What I learned took me on a journey to help create one of the most innovative approaches to mental health promotion I have ever seen.

Research suggests that male depression goes 50–65 percent undiagnosed. Why? Over different ages, nationalities, and ethnic and racial backgrounds, men are less likely to seek help. The trend is due in part on men’s socialization and in part on health delivery systems and their ability to identify their own symptoms.

Gender role socialization theories share a perspective that helps explain these statistics.1 Cultural codes of achievement, aggression, competitiveness, and emotional isolation are consistent with the masculine stereotype; depressive symptoms are not. Cultural ideals of rugged individualism lead to social fragmentation and fewer coping alternatives. When men consider seeking help, they often go through the following series of internal questioning.

- Is my problem normal? The degree to which men believe other men experience the same problem affects their decision to seek help. A prime example of this psychological process is erectile dysfunction. Before Senator Bob Dole’s public disclosure, many men thought they were the only ones suffering from this highly common and highly treatable problem. After the public campaign, many more men sought help.

- Is my problem central to who I am? If the mental health symptoms reflect an important quality about the person (for example, the hypomania in bipolar disorder that impacts creativity or productivity), then the person will be less likely to seek help.

- Will others approve of my help-seeking? If others, especially other men, are supportive, then the person will be more likely to go. Help-seeking is particularly likely if the group is important to the person and unanimous in their support.

- What will I lose if I ask for help? For many, the biggest obstacle to asking for help is fear of losing control: losing work privileges or status, being “locked up,” or losing one’s friends or family.

- Will I be able to reciprocate? Usually, the mental health services offered do not allow opportunities for reciprocity. Because of ethical standards, the mental health practitioner is often not allowed to share personal information or receive favors, thus maintaining a position of power over the client. For some men, receiving help is acceptable only if they can return the favor later on; in the relationship with a mental health provider, this is often not possible. One exception is Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). According to their mission, “Alcoholics Anonymous is a fellowship of men and women who share their experience, strength and hope with each other that they may solve their common problem and help others to recover from alcoholism.” According to the AA fact file, men make up 65 percent of membership in AA, indicating that this model of reciprocity is appealing to men. By contrast, among persons with any recent mental health disorder, a higher percentage of women (16–26 percent) made mental health visits than men (9–15 percent). These data suggest that historical, traditional approaches to reaching men with mental health and suicide prevention messages have been mostly unsuccessful, and new, innovative approaches need to be explored and developed.

Man Therapy: An Innovative Solution

“Man Therapy” is a new approach to reaching the “double jeopardy” man—the man who lives with a number of risk factors for suicide and is least likely to reach out for help himself. At the outset of the program development, the Man Therapy creators (myself, the creative geniuses at Cactus—a full-service advertising agency—and the public health folks at Colorado’s Office of Suicide Prevention) sought to fill the gap of the lack of comprehensive prevention efforts targeting men in the face of increasing suicide rates for men in the middle years. The team decided to take an unapologetic, bold stance to reach those men most vulnerable for suicide risk and developed Dr. Rich Mahogany, a fictional therapist, to help translate the issue and solutions of mental health into a language that resonated with this subgroup of men.

Dr. Mahogany is the focal point of Man Therapy. This character strategically uses maladaptive ideas of masculinity to bridge to new ideas that help men reshape the conversation of mental health, often using dark humor to cut through stigma and tackle issues like depression, divorce, and suicidal thoughts head on. The creators’ decision on this approach was steadfast, despite some initial pushback from some in the mental health community who were concerned we were making light of a serious topic or those supporting the men’s movement who were discouraged that we chose to bring stereotypes of masculinity into the project. When we asked, our target demographic told us that using humor and “man speak” resonated with them and helped them think about their mental health in a different way.

What Is Man Therapy?

Man Therapy is a program that uses compelling, humorous media—television, radio, billboards, print media, and social media—to drive men to the “Man Therapy” website portal (www.ManTherapy.org). At the website, men can meet Dr. Mahogany and take the 20-point head inspection. The results help answer the question “How bad is it?” when it comes to their depression, anxiety, substance use issues, or anger. When men indicate their level of distress is high, Dr. Mahogany refers them to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline or other crisis support services. When their distress is midrange, he offers various forms of mental health services and peer support. When they are showing resilience and mental fitness, he encourages them to keep up the good work of building their psychological hardiness.

Overarching goals for Man Therapy include the following.

- To improve social norms around mental health among men and the general population

- To increase help-seeking behavior among men for a variety of health and mental health issues, leading to an increase in men seeking available resources (including those provided on the site)

- Long-term: to reduce rates of suicidal ideation and deaths among men

Based on the results, the website then helps link the man to specific resources based on his presenting concerns. Some are self-help tips, others are external resources, and some are inspirational videos of real men in recovery.

Because the original program was so successful, the creators develop new modules to meet the needs of specific men—such as male veterans and first responders. We also developed some new media for primary care professionals who might come into contact with a man in distress.

Does Man Therapy Work?

Before we launched Man Therapy, we spent a long time asking a number of men and people who surrounded men in crisis “What would work?”

We listened to focus groups comprised of men’s support systems and others in a position to pick up on changes in their mood and behavior: employee assistance professionals, human resources professionals, members of various faith communities’ pastoral care, spouses, and other mental health professionals.

In addition, in-depth interviews were conducted with men who had experienced a suicide crisis (attempt or aborted attempt) as an adult and who were now at least 2 years past this event and considered to be thriving. After a thematic analysis of the transcribed interviews and focus groups, the Man Therapy team concluded that the following approaches would increase success in reaching high-risk men of working age.

- Approach #1: Soften the mental health language out of the initial communication with men. Many at-risk men were not seeing their problems through a mental health lens, so communication such as “if you are depressed, seek help” was missing an important subgroup of men.

- Approach #2: Show role models of hope and recovery. The men suggested that stories of men with “vicarious credibility” who have gone through tough times and found many alternative ways to healing would offer hope that change is possible.

- Approach #3: Connect the dots: physical symptoms with emotional issues. Men were more willing to acknowledge changes in energy, sleep patterns, and appetite but did not always recognize how they were tied to mental health concerns.

- Approach #4: Meet men where they are instead of trying to turn them into something they are not. The research participants emphasized the importance of compelling messaging using humor, especially dark humor, to break down social barriers. Rather than expect men to find information in our mental health centers, the messages needed to show up in locations men frequent and through media targeting men. Finally, the research revealed an approach to reach men using an Internet-based strategy that allowed for anonymity and self-assessment.

- Approach #5: Offer opportunities to give back and make meaning out of the struggle. Even men conditioned to never ask for help often do so when they have an opportunity to return the favor—one helps another clean the gutters knowing next weekend he will return the favor and help move the dishwasher to the dump. The research indicated that children and a desire to leave a positive legacy were often important barriers to engaging in suicidal behavior. Volunteering, spiritual growth, and strengthened relationships were also helpful in finding meaning after despair and creating a sense of belonging. For these reasons, the team looked for ways men could engage in reciprocity in the help-seeking, help-giving cycle.

- Approach #6: Coach the people around the high-risk men on what to look for and what to do. Several points of research indicated that intimate partners were both the most likely cause for suicidal distress (e.g., divorce, separation, death) and the most likely person to intervene and influence a man to seek help. In addition, research uncovered that workplaces needed training, just like CPR, to help coworkers identify suicidal distress and refer to helpful resources. Because of these discoveries, the mental health program needed not only to target men but also work to reach the people who surrounded men in crisis.

- Approach #7: Give men at least a chance to assess and “fix themselves.” As one in-depth-interview participant said, “Show me how to stitch up my own wound like Rambo.” The blueprint for change needed to offer mastery-oriented intervention strategies that demonstrate progress and were time-limited. Simple, self-help strategies would allow men to take action in smaller, concrete steps.

Man Therapy: Scope and Outcomes

Preliminary evaluation efforts demonstrate that the program is reaching the desired target audience and having the intended effect.

- 78 percent of viewers are male.

- 78 percent are between the ages of 25–64.

- 15 percent are active duty military or veterans.

- 83 percent would recommend the website to a friend in need.

- 73 percent said the 20-point head inspection helped direct them to the appropriate resources on the Web.

- 51 percent said that they agreed or strongly agreed they were more likely to seek help after visiting the website.

When asked what was the thing they liked best about Man Therapy, participants spontaneously responded “the humor” and told us things like: “The use of humor with this topic is incredibly important. The last place that a person struggling wants to go to is a ‘sterile’ site that sucks out that last bit of dignity.”

To date, almost 800,000 unique visitors have come to the website portal, resulting in almost 325,000 people completing the 20-point head inspection and 33,000 people accessing crisis services. Viewers have spent an average of 5–7 minutes on the website, which means most are taking their time to explore the many resources there.

Conclusion

Through humor and digital media, Dr. Mahogany has reached almost a million men internationally, helping them consider mental health as part of overall health and making mental health services more accessible. In conclusion, Man Therapy and the innovative strategies the program employs hold great promise for being the bridge between men struggling with mental health problems and the interventions that can save their lives.

1Joe Conrad, Jarrod Hindman, and Sally Spencer-Thomas, Man Therapy: An Innovative Approach to Suicide Prevention for Working Aged Men, ManTherapy.org, July 17, 2012.

Opinions expressed in Expert Commentary articles are those of the author and are not necessarily held by the author’s employer or IRMI. Expert Commentary articles and other IRMI Online content do not purport to provide legal, accounting, or other professional advice or opinion. If such advice is needed, consult with your attorney, accountant, or other qualified adviser.

Article originally published on International Risk Management Institute (IRMI): https://www.irmi.com/articles/expert-commentary/man-therapy-engaging-men-in-their-mental-health