Why Should Workplaces Care About Suicide Prevention

1. Work’s relationship to suicide.

When working well, work fosters social relationships and offers people a place of purpose and solidarity. When social structures like work disintegrate, the individual suffers, and sometimes suicide can be a consequence. When workers are only seen as a source of profit or an obstacle to profit, suicidal despair may result due the disconnection people feel.

The increased attention to “mental health literacy” at work may in part be a deflection away from the importance of these findings. If workplaces believe that the mental health symptoms and suicide crises

are only due to untreated or mistreated mental illnesses, they may be engaging in a “state of denial” about their own systemic contribution to the problem. One tactic used to minimize workplaces’ role is by medicalizing suicide as being the sole result of individual psychopathology rather than anything linked to work conditions.

2. The cost of suicides and suicidal behavior on workplaces.

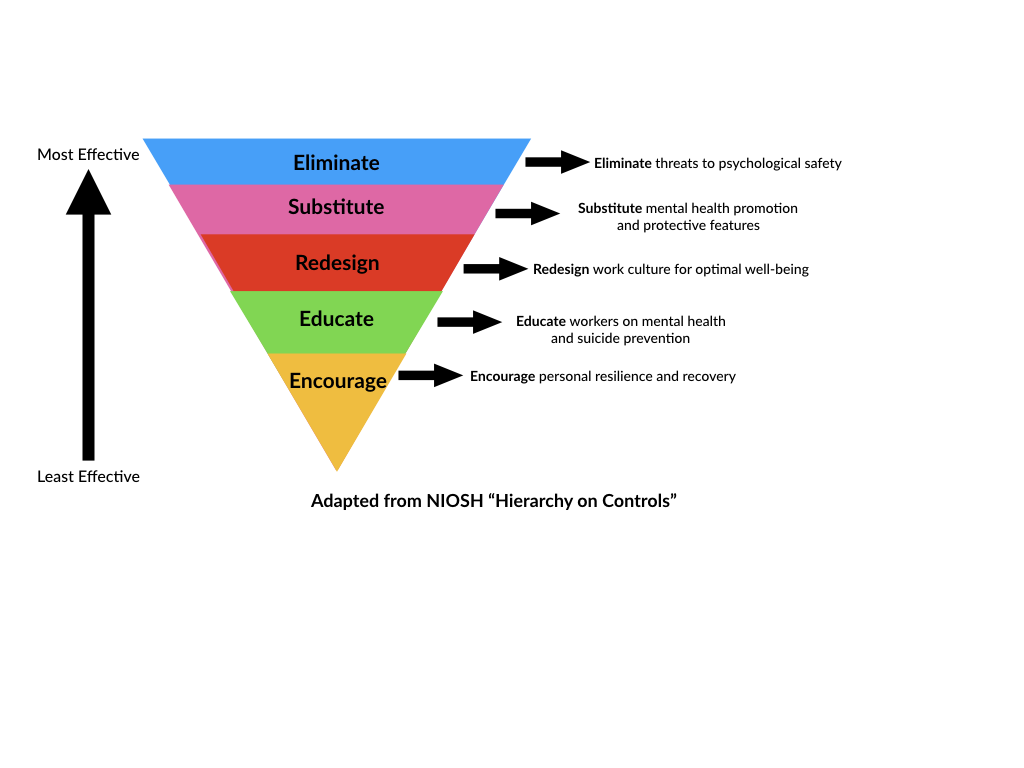

Recently, a team of health economists(1) have been studying the costs of suicide and the return on investment of suicide prevention and intervention activities to workplaces and communities. For instance, they found that on average the cost of a suicide death of one male construction worker was $2.14 million, mostly due to the average 27.3 years of productive employment lost . They also determined that for every dollar invested in suicide prevention $4.60 would be returned to society. Another study measured a number of costs related to suicide and suicidal behaviors including production disturbance (e.g., value of lost production and staff turnover), human capital lost, medical costs, administrative costs (e.g., due to employer investigation), and more.(2) They examined the costs associated with short- and long-term absences after a suicide attempt, full incapacity and fatality and found a 1.50:1 benefit cost ratio for investing in suicide prevention. Not all suicide prevention is crisis oriented; in fact, proactive efforts may even have a bigger ROI. Just like promoting heart health is less expensive that responding to the crisis of a heart attack, promoting optimal and holistic well-being makes good business sense. Rather than only focus on deficit or symptom-focused models of workplace intervention many positive psychological resources can also be cultivated like self- esteem, mastery, resilience and emotional intelligence. Well-being has clear connections to greater employee engagement, proactive work behavior, and transformational leadership(3). All together, promoting protective factors, early intervention and effective suicide crisis response save companies money and heartache.

Лечение алкоголизма – клиника в Твери “Рецепт свободы”

3. Suicide waves in industries and legal action.

In 2012 the Chief Executive of France’s Telecom was forced to resign and six other executives faced legal action taken against the company following an investigation. Charges filed against the company were related to workplace bullying, harassment and toxic “management-by-terror” practices that were allegedly connected to over 80 employees’ suicide attempts or deaths. Around the same time another similar suicide wave emerged in a different part of the world. China’s Foxconn, a telecommunications company that supports the manufacturing of Apple products, also experienced a suicide cluster in 2010 and underwent highly public scrutiny. At one point 300 workers allegedly took to the roof of Foxconn and threatened to jump unless they were treated more fairly. Other “suicide waves” connecting work to suicidal despair have been noted in other cultures and industries including Australian miners, British bankers, Indian farmers and Japanese managers. In fact, the Japanese even have a work describing suicide from overwork — karo-jisatu — and consider the problem an urgent public health issue. In the United States we have also seen surges of highly publicized suicide deaths related to work including numerous banker deaths in 2015 and a current surge in first responder suicide deaths.

4. Job strain and suicide.

Toxic work demands along with negative employee perceptions of the work environment have been historically under-appreciated in the conversation about suicide prevention; however, research connects a number of job stress-related factors to risk of suicide death and attempts, even when controlling for mental health problems including:

- Lack of job autonomy

- Lack of job variety

- Work-family conflict (i.e., work demands make family responsibilities more difficult)

- Family-work conflict (i.e., family demands make work role challenging)

- Heightened job dissatisfaction and the feeling of being “trapped”

- Work that was not meaningful or intrinsically rewarding

- Low job control — lack of decision-making power and limited ability to try new things

- Lack of supervisor of collegial support — poor working relationships

- Excessive job demands and constant pressure/overtime

- Effort-reward imbalance — related to perceived insufficient financial compensation, respect/ status

- Job insecurity — perceived threat of job loss and anxiety about that threat

- Bullying, harassment and hazing at work

- Prejudice and discrimination at work

- Work-related trauma

- Work-related sleep disruption

- Toxic work-design elements (exposure to environmental aspects that cause pain or illness)

- Work culture of poor self-care and maladaptive coping (e.g., alcohol and drug use)

“It is clear that job stressors are associated with increased risk for suicide. Thus, job stress prevention and control should be a key component of workplace…suicide prevention strategies,”

– Dr. Allison Milner, Mental Health in the Construction Industry (4).

5. Workplace fatalities.

Worker safety is a core value in many industries, and thus safety directors routinely pay attention to trends in workplace morbidity and mortality. Because most suicide deaths do not occur at a worksite, suicide has not historically been “on the radar” of safety professionals. When a workplace fatality happens, the cause is almost always determined to be “accidental” and a deeper investigation into intent to die is not undertaken. Because this deeper investigation is not done, the only remedy suggested is more safety training. While safety training will help those who did not intend self-harm, it will not benefit those whose death is intentional. When we look at the fatal occupational injuries(5), the first two most common (transportation incidents and falls) are also common ways people think about taking their lives(6,7). Thus, it is possible that some, if not many, of these workplace fatalities are actually suicide deaths, which then means that safety training may not be effective in preventing them.

When a suicide occurs at a job site, the work is halted indefinitely as law enforcement conducts an investigation and traumatized workers are unable to function. When a suicide impacts a workplace, the grief and trauma of co-workers can linger a very long time; sometimes after a suicide at work people feel too traumatized to return. Other industries like construction and transportation companies note that suicide deaths can completely stop operation for hours and even days while the company remains responsible for continued payment for all employees and deliverables to clients.

When a company or even an industry has been known to be prone to suicide, people become afraid that their health may become in jeopardy if they work in this area.

1.Doran C, Ling R, Gullustrup J, Swannell S, et al. The impact of a suicide prevention strategy on reducing the economic cost of suicide in the New South Wales construction industry. Crisis. 2016;37(2):121-9.

2. Kinchin I, Doran C. The economic cost of suicide and non-fatal suicide behavior in the Australian workforce and the potential impact of a workplace suicide prevention strategy. Int J Environ Pub He. 2017;14(347):1-14.

3. Milner A, Law P. Summary Report: Mental Health in the Construction Industry. 2017. http://micaus. bpndw46jvgfycmdxu.maxcdn-edge.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/MIC-QLD-construction-industry- roundtable-report.pdf Accessed February 11, 2019.

4.Milner A, Law P. Summary Report: Mental Health in the Construction Industry. 2017. http://micaus.bpndw46jvgfycmdxu.maxcdn-edge.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/MIC-QLD-construction-industry- roundtable-report.pdf Accessed February 11, 2019.

5.Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries. Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI) – Current and Revised Data. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2017. https://stats.bls.gov/iif/oshcfoi1.htm#2017 Accessed April 8, 2019.

6.Crosby A, Cheltenham M, Sacks J. Incidence of suicidal ideation and behavior in the United States, 1994. Suicide Life-Threat. 1999;29(2):131-140.

7.DeAnrade D, DeLeo D. Suicidal behavior by motor vehicle collision. Traffic Inj Prev. 2007;8(3):244-247.